When was Alzheimer’s disease discovered?

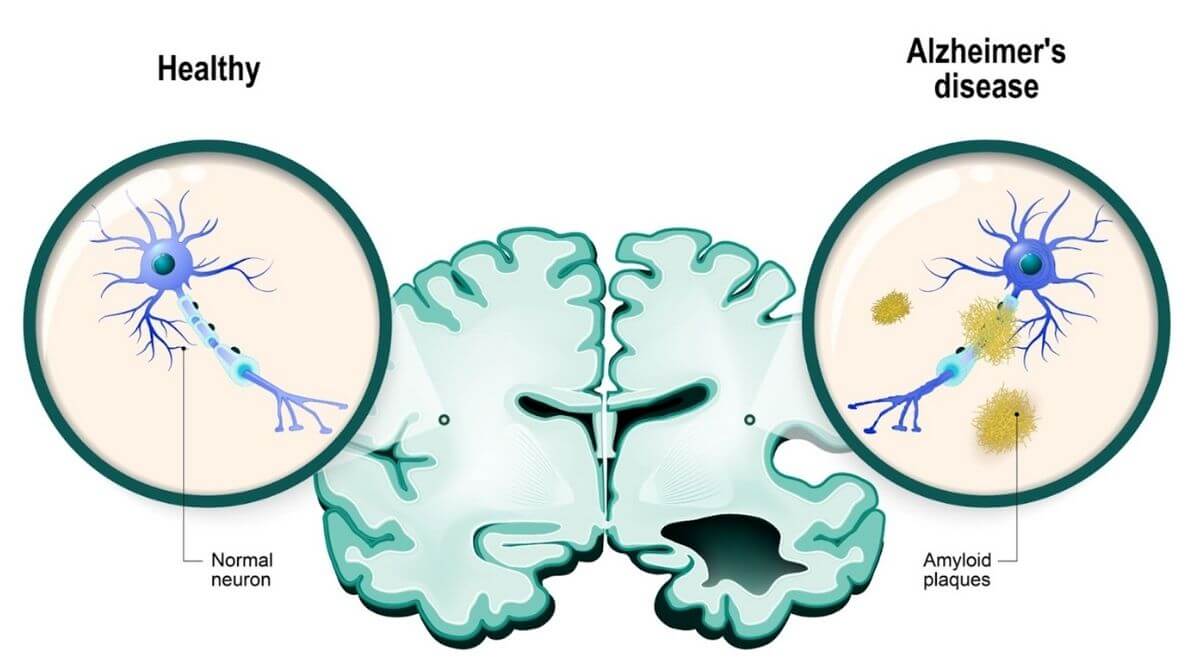

Alzheimer’s disease as we know it was first described by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German doctor, in 1906. He was one of the first physicians known for linking mental illness symptoms to brain changes in his patients. His patient, Auguste Deter, was the first described case of the disease when her husband became concerned over increasing memory loss and mental changes at the age of 50. She died soon after at the of 51 when Dr. Alzheimer examined her brain for microscopic changes, and he found the pathologies known as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The disease, of course, was later named after Dr. Alzheimer, and is now known to be the leading cause of dementia.

What causes Alzheimer’s disease?

The search for a single cause of Alzheimer’s disease has been ongoing since Dr. Alzheimer first described the disease. Many hypotheses have emerged to explain the disease. To aid this research, the U.S. Congress started the National Institute on Aging in 1974 as the primary source of federal funding for Alzheimer’s research. Shortly after, the “cholinergic hypothesis” arose in the late 1970s, suggesting the cause as a deficit in the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. This hypothesis led to the development of many FDA-approved drugs that are still in use today; however, these drugs do nothing to modify the course of disease.

The next major hypothesis, known as the amyloid cascade, revolves around the discovery of beta-amyloid (Aβ) in plaques in 1987. Scientists began identifying mutations that increased the amount of Aβ in the brain causing the buildup and toxicity of this protein, such as the amyloid precursor protein (APP). Since then, multiple risk factor mutations have been identified including apolipoprotein-E (APOE) and presenilin 1 and 2 (PSEN1 or 2), among others. The amyloid cascade hypothesis has driven and still drives much of the Alzheimer’s disease research to date, focusing on either Aβ in plaques or the neurofibrillary tangles. The protein responsible for these tangles is tau, which normally aids in the function of our nerve cells but can collapse causing the insoluble twists found in patient brains. The researched focused on the amyloid cascade is also complemented by a variety of science focused on lifestyle choices, inflammation, metabolism, and the role of the blood-brain barrier or infections in developing Alzheimer’s disease.

How does Alzheimer’s disease progress?

Alzheimer’s disease presumably starts by some event(s) causing the misfolding and accumulation of amyloid proteins. The buildup of amyloid begins during the asymptomatic, or symptom-free, phase of disease which may last for years. The presence of amyloid deposits may in asymptomatic patients could be detected using amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) scanning or by evaluating the cerebrospinal fluid of patients. These tests may be performed in patients that have a genetic predisposition or family history of illness.

Oftentimes, the tests are performed to diagnose patients that are beginning to display symptoms in the pre-dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease. In this phase, patients begin to have difficulty with daily tasks and cognitive functions but maintain their independence. Alzheimer’s disease progressively worsens, and patients experiences further cognitive decline and behavioral changes, requiring help from loved ones or caregivers to assist with daily living. In the late stage of Alzheimer’s disease dementia, patients require full-time care.

What are the treatment options for Alzheimer’s disease?

In the last decade, funding for Alzheimer’s disease has exploded as scientists search for effective disease-modifying therapeutic options. Unfortunately, the disease is very complex, decreasing the likelihood that researchers will be able to find a catch-all drug that treats every patient with Alzheimer’s disease. Many patients are not diagnosed with Alzheimer’s before symptoms begin which complicates the development of successful drugs. Ideally, there will someday be effective therapeutics that can slow disease at any stage, but it is more likely that this can be achieved in the early phases of Alzheimer’s.

Many FDA-approved drugs exist for patients that allow them to manage their symptoms. In 2021, the FDA approved its first disease-modifying drug, aducanumab, for its ability to reduce the amyloid buildup in the brain; however, aducanumab was tested in patients with early-stage disease. This means it has yet to be determined if it can alter the clinical progression of dementia in patients in later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Unfortunately, because aducanumab is an antibody that attaches to plaques, it may also have adverse effects such as brain swelling or bleeding as the immune system works to clean up the plaques.

Scientists continue to investigate and discover different options for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Hundreds of clinical trials for various Alzheimer’s disease drugs or interventions are currently underway as scientists and physicians work to improve the lives of patients. Many lifestyle choices such as physical activity and adequate sleep have been linked to a decreased risk of dementia which has led many to investigate the underlying mechanisms and how they can be used as interventions in Alzheimer’s disease. As we continue to learn more about the underlying disease processes, we can continue to expand the arsenal of drugs that are available to not only treat the symptoms but modify the disease course of Alzheimer’s.